|

This is the third installment in my series responding to James White's book The King James Only Controversy. In this article, I respond to several of White's claims regarding Codex Sinaiticus, one of the main Greek manuscripts used for the modern translations. Chapter 3: Textual Criticism

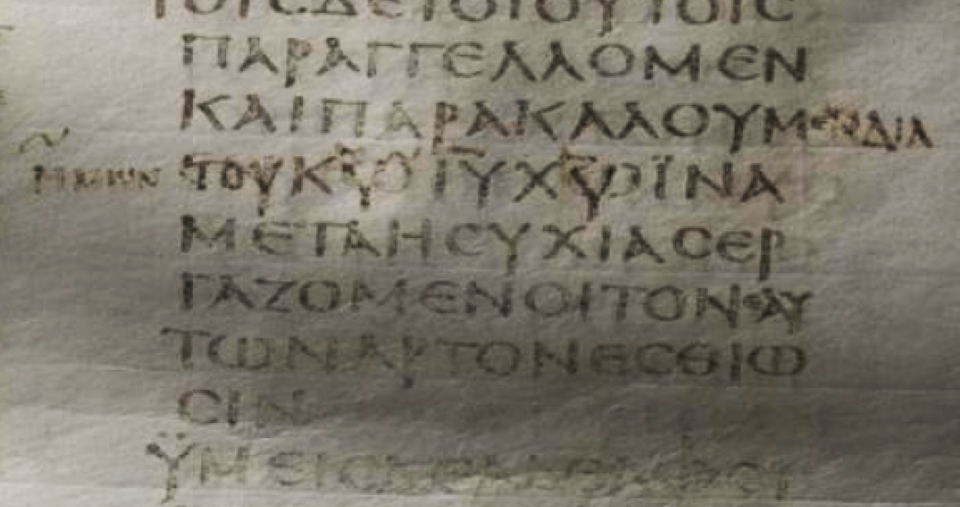

The third chapter of White's book begins with a grand display of White's typical passive-aggressive condescension toward those who dare to disagree with him. He asserts that the KJV Only controversy wouldn't even exist "if most Christians had a solid grasp on the history of the Bible." A short while later, he adds that "KJV Only advocates are not generally interested in discovering the real reasons why the modern translations do what they do." (emphasis in original) And he claimed that it is a "lack of study" that "provides the breeding ground of the KJV Only controversy." These are not the words of someone who is writing "because of a desire for peace in the church" as White claims. The prevalence of these kinds of low-brow ad hominems in White's speaking and writing should be a concern to all those who follow him. As White moves to the meat of this chapter, he asserts that Codex Sinaiticus is "a great treasure, for a while the oldest manuscript known." This claim is inaccurate. It is far from certain whether Codex Sinaiticus is one of the oldest manuscripts known. There is a competing claim that Sinaiticus is a 19th century manuscript. When Tischendorf published a printed copy of the text of Codex Sinaiticus, a gentleman by the name of Constantine Simonides claimed that Tischendorf had merely "discovered" a Bible that Simonides, a renowned calligrapher, had created. Simonides claimed to have given his creation to the monastery in Sinai where Tischendorf later "discovered" it. The dispute between Tischendorf and Simonides was the subject of a significant amount of debate among the scholars of that day, and much was written about it in both scholarly journals and public newspapers, and it has continued to be debated by scholars even to this day. White's veneration of Codex Sinaiticus is typical of those who prefer the critical text, but there is solid evidence in support of the contrary claim made by Simonides. An excellent overview of the evidence supporting Simonides can be found in the book Neither Oldest Nor Best by David H. Sorenson published in 2019. Unlike White, Sorenson relies heavily on original source material, and he reproduces several of those original sources in their entirety as part of his book. Sorenson presents multiple lines of evidence to support his position, but the one that I find the most convincing is Tischendorf's own admission that Sinaiticus was a recent manuscript. Prior to Tischendorf's "discovery" of Codex Sinaiticus, Simonides travelled to Leipzig with a copy of the Shepherd of Hermas from Codex Sinaiticus. The scholars at Leipzig thought that this was an ancient Greek manuscript, but when Tischendorf examined it, he denounced it as a recent creation because it contained modern words and phrasings that were not found in ancient Greek literature. Then, when Tischendorf "discovered" Codex Sinaiticus, he realized that the copy of Shepherd of Hermas in Sinaiticus was the same as the one in Leipzig that he had denounced just a few years earlier, and he wrote a retraction claiming that the Leipzig manuscript must indeed be ancient because it agreed with Codex Sinaiticus. The problem with Tischendorf's retractions is that the modern words and phrasings are just as obvious in the Sinaiticus copy of Shepherd of Hermas as they are in the Leipzig manuscript. Barring the possibility of time travel, there is no way that the Shepherd of Hermas found in Codex Sinaiticus is an ancient copy. It was written in a modern Greek not in Koine Greek. And since the Sinaiticus copy of the Shepherd of Hermas is an integral part of Codex Sinaiticus, the entire Codex must be of recent origin as Simonides claimed.[1] White moves on from his veneration of Sinaiticus to discuss the differences between the critical text and the TR. White claims that: "The simple fact of the matter is that no textual variants in either the Old or New Testaments in any way, shape, or form materially disrupt or destroy any essential doctrine of the Christian faith. That is a fact that any semi-impartial review will substantiate." This sounds like a bold claim by White, but it's really just a cop-out. When God gave His Word, he already knew that it would be copied by hand thousands of times to be distributed all around the world. He knew that there would be thousands of translations produced, and He knew that some of those copies and translations would be corrupted either by mistake or intent. God, in His great wisdom, chose to use so much redundancy that the essentials of the faith would still be present even if three-fourths of the biblical text were to be lost entirely. This is a testament to God's great wisdom and His care for us. It is not an excuse for accepting errors in a biblical text or translation. I see three problems with White's cavalier attitude toward textual variants. First, White's view cheapens the value of the Bible. We don't seek a perfect text just out of a desire to preserve the minimum essential doctrines of Christianity. We seek a perfect text so that we can preach "the whole counsel of God." Maybe White is content with simply knowing that the basics have been preserved, but I'm not. I want to know and understand everything that God said in Scripture, and having studied this issue for myself, I have the assurance that the complete Word of God is available to me not just the "98.33 percent" that White recognizes. Second, White's view is not consistent with Scripture. In the third chapter of Galatians, the Apostle Paul made a logical case for the primacy of faith over the Law. Paul's entire argument in this passage hinged on the ending of the word "seed" in the Abrahamic covenant. As Paul pointed out, God did not make a promise to Abraham and to his "seeds, as of many; but as of one, And to thy seed, which is Christ" (Galatians 3:16). Paul based an entire doctrine on the difference between a singular word and a plural word. Paul's argument demonstrates the importance of accuracy in the preservation of the biblical text even down to the smallest of details. What if there were a textual variant in which the word "seed" in the Abrahamic covenant had been changed to the word "seeds"? It's only a difference of two tiny letters in Hebrew. If an ancient Hebrew scribe had decided that this word should be written in the plural form because it was used with plural verbs and pronouns, then we would have good reason to reject that particular manuscript on the grounds that it would contradict Paul's argument in his Epistle to the Galatians. Even if all the surviving Hebrew manuscripts were pluralized in this way, we would still be confident in concluding that they must all be corruptions of an original that used the singular form of "seed" instead of the plural. The Bible is inerrant in the tiniest of details. Any reading which violates the doctrine of inerrancy must be invalid regardless of which manuscripts include it. This brings us to the third problem with White's attitude toward textual variants which is that there actually are places where important doctrines are contradicted by the textual variants adopted as part of the critical text. For example, the TR for John 7:8 has Jesus telling His brothers "I go not up yet unto this feast; for my time is not yet full come." The critical text, on the other hand has Jesus saying "I am not going up to this feast, for my time has not yet fully come." Both texts record that Jesus went up to the feast some time after His brothers left. Thus, the critical text claims that Jesus lied to his brothers while the TR does not. I mentioned before that we would reject any Hebrew manuscript that used the plural form of "seed" in the Abrahamic covenant, and that same reasoning should be applied to John 7:8. The Bible tells us that Jesus is God, and it also tells us that God cannot lie. Therefore, the textual variation that makes Jesus out to be a liar should be rejected as a corruption of the original text because it contradicts the doctrine of the deity of Christ. Similarly, there are two separate prophecies referenced in Mark 1:2-3, and the TR attributes these two prophecies to "the prophets." The critical text, on the other hand, claims that these prophecies are from Isaiah. In the KJV, Mark 1:2-3 reads as: "As it is written in the prophets, Behold, I send my messenger before thy face, which shall prepare thy way before thee. The voice of one crying in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make his paths straight." In the ESV, this passage reads as: "As it is written in Isaiah the prophet, “Behold, I send my messenger before your face, who will prepare your way, the voice of one crying in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make his paths straight,’”" The first of these two prophecies is found in Malachi 3:1 which says: "Behold, I will send my messenger, and he shall prepare the way before me." The second prophecy is found in Isaiah 40:3 which says: "The voice of him that crieth in the wilderness, Prepare ye the way of the LORD, make straight in the desert a highway for our God." The reading found in the critical text is erroneous and contradicts the doctrine of the infallibility of God and the doctrine of the inspiration of Scripture. White's insistence that no doctrines are harmed by his position is demonstrably false. Earlier in the chapter, White claims that "One can, by comparison of these many, many manuscripts, reproduce the original,” but this is not how scholars arrived at the critical text. The Critical Text is not based on a comparison of thousands of manuscripts. It is based on the philosophy that the majority of manuscripts should be ignored in favor of the readings found in an extremely small selection of what they consider to be the oldest manuscripts. White uses the division of the text into two major families of Alexandrian and Byzantine to disguise the fact that he is rejecting the wording found in the vast majority of the manuscripts in favor of wording found in only a few and sometimes only one manuscript. The critical text also ignores the vast collection of early translations and quotations of the Bible. John Burgon pointed this out to great effect in his book The Revision Revised. Burgon noted that "The necessity of translating the Scriptures into divers languages for the use of different branches of the early Church, procured that many an authentic record has been preserved of the New Testament as it existed in the first few centuries of the Christian era.”[2] Regarding the quotations of Scripture by early Christians, Burgon wrote "the requirements of assailants and apologists alike, the business of Commentators, the needs of controversialists and teachers in every age, have resulted in a vast accumulation of additional evidence, of which it is scarcely possible to over-estimate the importance. For in this way it has come to pass that every famous Doctor of the Church in turn has quoted more or less largely from the sacred writings, and thus has borne testimony to the contents of the codices with which he was individually familiar."[3] Burgon's writings are literally filled with examples of ancient translations and quotations that agree with the readings found in the TR. These translations and quotations confirm that the Byzantine readings are at least as old as if not older than the Alexandrian readings. Toward the end of the chapter, White presents several examples of differences between the Alexandrian text family and the Byzantine text family, and he asserts that all of those changes are the result of an "expansion of piety." According to White, this is a "perfectly logical explanation" that "requires no special theories," but he fails to grasp that "expansion of piety" is itself a "special theory." As far as I know, there are no records of a New Testament copyist admitting that he changed the words of the Bible out of a desire to "protect and reverence divine truths." White is doing nothing more than making a fallacious appeal to motive. This is a variant of the circumstantial form of the ad hominem fallacy. White has no idea what the motives were for any of the New Testament copyists. Plus, there are many cases that go the other direction where the reading in the older manuscripts is more pious than that found in more recent manuscripts. James Snapp, Jr. has catalogued a list of 40 such cases in the Gospels alone.[4] White's position cannot account for these cases. Continue reading: Part 1, Part 2, Part 4 [1] David H. Sorenson, B.A., M.Div., D.Min., Neither Oldest Nor Best (Duluth, MN, Northstar Ministries, 2019), 115-122 [2] John William Burgon, B.D., The Revision Revised, (New York, Dover Publications Inc., 1971), 35 [3] Ibid [4]https://www.thetextofthegospels.com/2019/03/challenging-expansion-of-piety-theory.html

1 Comment

|

Bill Fortenberry is a Christian philosopher and historian in Birmingham, AL. Bill's work has been cited in several legal journals, and he has appeared as a guest on shows including The Dr. Gina Show, The Michael Hart Show, and Real Science Radio.

Contact Us if you would like to schedule Bill to speak to your church, group, or club. "Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser: teach a just man, and he will increase in learning." (Proverbs 9:9)

Search

Topics

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed