|

One of the tests that I use for determining the validity of a biblical text or translation is the test of inerrancy. This is one of the primary reasons that I prefer the Textus Receptus over the critical text. If the Word of God is inerrant, then the critical text cannot be the pure Word of God, for it contains many errors that are overlooked simply because the compilers of that text do not hold to the doctrine of inerrancy.

0 Comments

Over the past few years, I've had several friends ask me for my opinion of Mark Ward's book Authorized: The Use & Misuse of the King James Bible. I read the book after the first request, and I found Ward's arguments to be both shallow and false. My position on the KJV is that it is currently the most accurate English translation of the purest Greek and Hebrew texts. I hold to that position for a variety of reasons drawn from my studies of theology, history, etymology, and linguistics. I expected Ward's book to present an intellectual challenge to my position. What I found instead was a childish and pedantic collection of arguments that did more to prove the ignorance of the author than to support his claims.

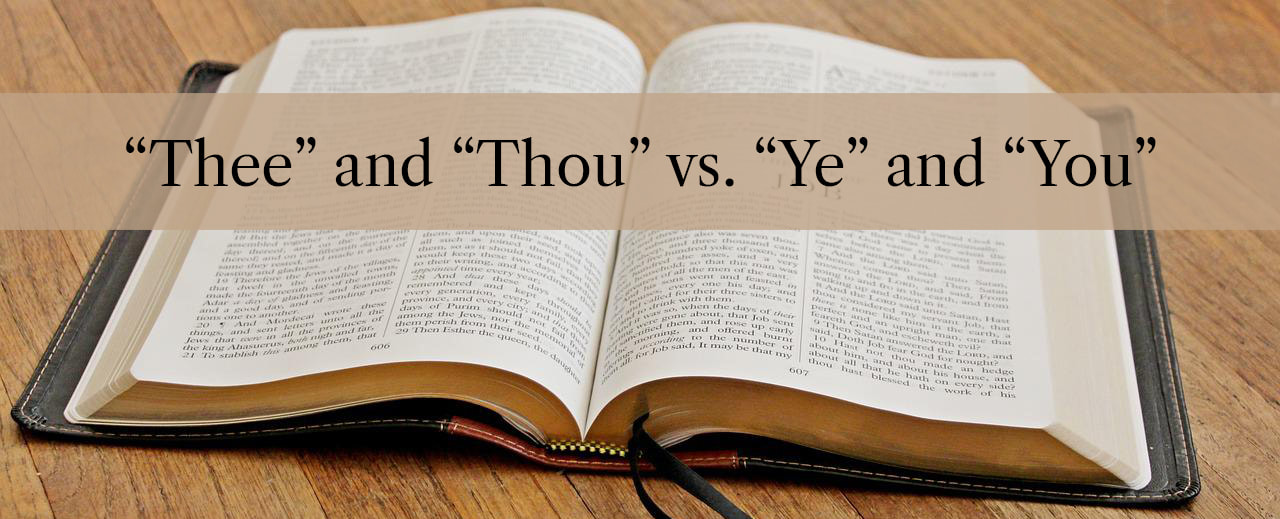

The "thee's" and "thou's" of the KJV are not merely antiquated language. These terms had actually fallen out of use by the time that the KJV was translated, but the translators recognized the need to resurrect this antiquated terminology in order to keep their translation as accurate as possible.

The content of the third lesson in this series begins on page 53 of Dean Burgon's The Revision Revised, and covers two examples of errors in the critical text. The first comes from Acts 18:7. It is very difficult to convey Burgon's explanation of this verse through a mere outline, so I will just let him speak for himself before proceeding to the next verse. Here is Burgon's explanation of the error contained in the critical text rendition of Acts 18:7:  Without fail, anytime that I bring up my preference for the Textus Receptus and the King James Version, I receive responses from people who assume that my position is based solely on a philosophical argument. I suppose that they are somewhat justified in coming to that conclusion, for most defenders of the TR and the KJV deal only with the philosophical arguments and seem to forget that their position has some very strong evidential support. The thing that I enjoy about Burgon's work is that he does not make this mistake. Burgon presents the philosophical arguments as a means of revealing the premises of both sides' arguments, and then he focuses most of his effort on testing those premises against the available evidence. In part 2 of my series, I presented Burgon's evidential analysis of Luke 2:14. My outline of Burgon's argument is provided below, and you can read his full statement beginning on page 41 of The Revision Revised.  I recently taught a five part series on textual criticism based on the works of Dean John Burgon and comparing the KJV with the ESV. In my opinion, Burgon represents the best arguments against the modern critical text, and the ESV represents the best translation of that text into English. Granted, Burgon's work is a bit dated, but many of his arguments are just as relevant today as they were when he first presented them more than 100 years ago. This is apparent by the accuracy of Burgon's arguments when compared with the ESV and the most recent editions of the critical text. So, without any further ado, here is the outline from part 1 of my series on textual criticism. |

Bill Fortenberry is a Christian philosopher and historian in Birmingham, AL. Bill's work has been cited in several legal journals, and he has appeared as a guest on shows including The Dr. Gina Show, The Michael Hart Show, and Real Science Radio.

Contact Us if you would like to schedule Bill to speak to your church, group, or club. "Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser: teach a just man, and he will increase in learning." (Proverbs 9:9)

Search

Topics

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed