It has become rather common in our day to hear descriptions of our founding fathers as bold rebels daring to defy the authority of the British government, but is that really what happened? Was the American Revolution an act of rebellion against England? That has certainly become a popular theme in modern, American education, but the records of the founding era tell a different story.

0 Comments

I recently had the opportunity to listen to a debate between Mark Hall and Steven Green on the topic of the Christian foundation of America. Hall has written a book defending the idea that America had a Christian foundation, and Green has written a book in defense of the opposite view. I obviously agree with Hall, but I thought that he could have done a better job of refuting some of Green’s claims (and he probably does so in his book). Since I was taking notes anyway, I thought that I would share a few of my objections to Green’s claims.

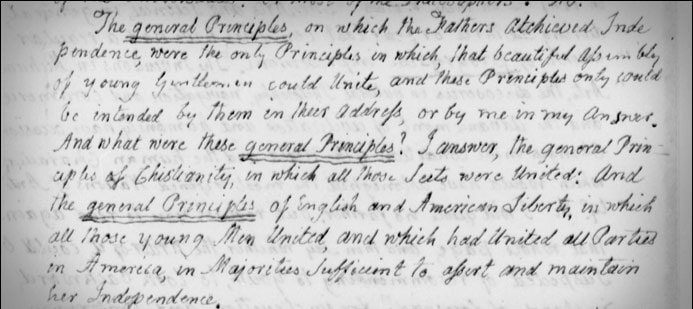

One of the major points of contention in the discussion of America’s Christian foundation is found in a reference that John Adams made to the “general principles of Christianity.” Those who support the idea that America was founded on Christian principles often present this statement as evidence in their favor, while those who disagree with them usually respond by pointing to the context of the statement as evidence for their position. Unfortunately, most of those discussing Adams’ statement seem to be operating under the impression that it was made in a vacuum. In this article, I will attempt to provide a full analysis of Adams’ letter and demonstrate that when we consider all of the variables in their proper order, it becomes clear that this letter supports the claim that America was founded on principles that are unique to Christianity.

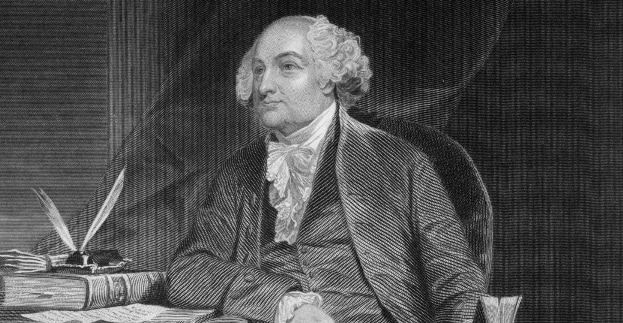

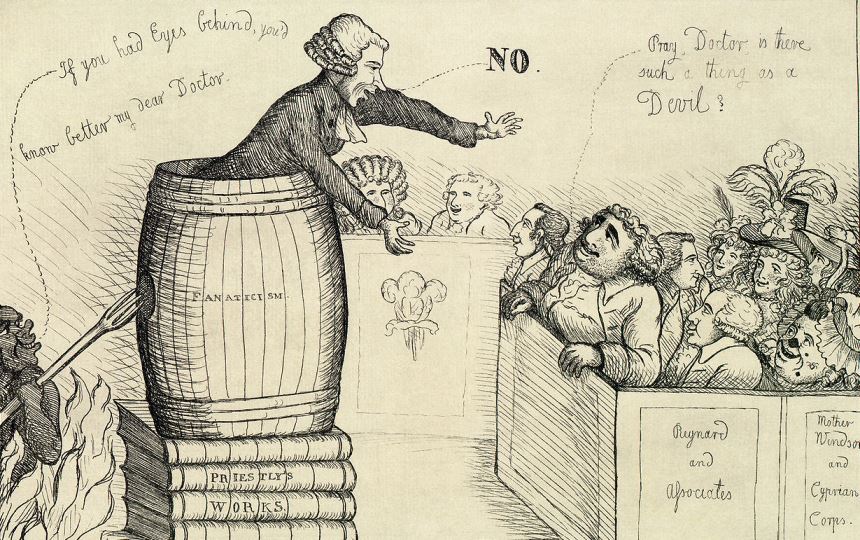

As part of his discussion of John Adams’ beliefs regarding the Bible, Frazer referenced a letter in which Adams mentioned an alternate version of the Ten Commandments. According to Frazer: In a discussion of an alternative set of the Ten Commandments, Adams suggested that [the] biblical record was unreliable—that “authentic copies” of the original were lost. In regards to John Adams’ view of the deity of Christ, Frazer wrote: However, like the deists, Adams did not believe in the deity of Jesus … For Adams and the other theistic rationalists, Jesus was an exemplary man who left an example to follow and who deserved to be imitated, but He was not God. Frazer is partly correct in this statement. Adams was a committed Unitarian who rejected the orthodox concept of the Trinity. In other words, he did not believe that Jesus Christ was the same being as God the Father. However, there are a very wide range of Unitarian views of Christ, and Frazer is mistaken to conclude that Adams believed Jesus to be just an exemplary man. In reading Gregg Frazer’s book on the founders, his high estimate of Joseph Priestley’s influence on the founding fathers is clear and blatant. Early in the book, Frazer writes that “It would be difficult to overstate the importance of Priestley to the development of the political theology of the American Founding.” In speaking of John Adams in particular, Frazer writes that he was “heavily influenced” by Priestley. Frazer further insists:

When discussing John Adams’ beliefs regarding the Bible, Frazer presented two references to an often quoted letter that Adams wrote to his friend Francois Van der Kemp. Frazer claimed that this letter is evidence of John Adams’ theistic rationalism because it presents both Adams’ acceptance of some revelation and his belief that the Bible is filled with fables. Unfortunately for Frazer, the letter in question does not support his claim that Adams believed the Bible to be filled with fables.  One of the most frustrating aspects of Gregg Frazer’s book The Religious Beliefs of America’s Founders is the abundance of errors that he blunders into when discussing the various theological positions that were debated during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Frazer has a tendency to assume that the theological terms which were in use at that time were understood in the exact same manner in which they are understood today. This can lead to some very serious misinterpretations as we can see in his discussion of Adams’ beliefs about the Bible. Frazer wrote of Adams that:  After criticizing John Adams for having a supposedly Deistic view of creation, Gregg Frazer decided to further condemn Adams for having a Deistic form of worship. This is a very interesting claim by Frazer for the simple reason that he never provided an explanation of how he thinks that true Christians ought to worship God. He did say at an earlier point in his book that Deists thought “the best way to worship God was to do good to and for one’s fellow man.” Yet Frazer never explained how this differs from the way in which a Christian ought to worship God or how it differs from the definition of pure religion given in James 1:27. |

Bill Fortenberry is a Christian philosopher and historian in Birmingham, AL. Bill's work has been cited in several legal journals, and he has appeared as a guest on shows including The Dr. Gina Show, The Michael Hart Show, and Real Science Radio.

Contact Us if you would like to schedule Bill to speak to your church, group, or club. "Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser: teach a just man, and he will increase in learning." (Proverbs 9:9)

Search

Topics

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed