|

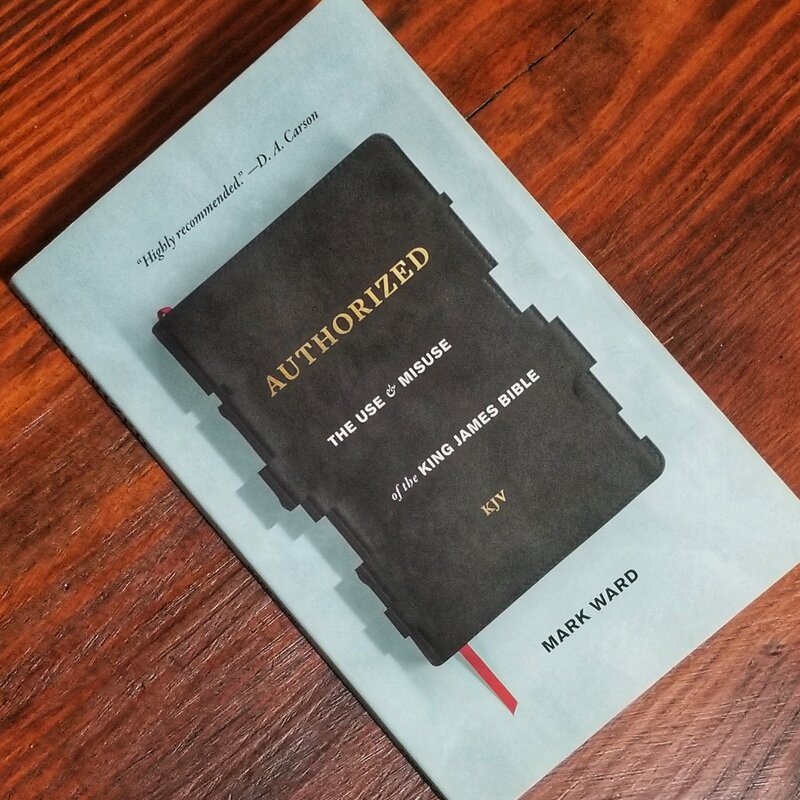

Over the past few years, I've had several friends ask me for my opinion of Mark Ward's book Authorized: The Use & Misuse of the King James Bible. I read the book after the first request, and I found Ward's arguments to be both shallow and false. My position on the KJV is that it is currently the most accurate English translation of the purest Greek and Hebrew texts. I hold to that position for a variety of reasons drawn from my studies of theology, history, etymology, and linguistics. I expected Ward's book to present an intellectual challenge to my position. What I found instead was a childish and pedantic collection of arguments that did more to prove the ignorance of the author than to support his claims. I was not planning to write a review of Ward's book, but I've shared an occasional thought about the book on Facebook, and I thought that it would be helpful to collect those posts into a single article for the benefit of my readers. So, without any further ado, here are a few of my thoughts on the book Authorized by Mark Ward:

1. What does "commendeth" mean? I'm reading through the book Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible. The author, Mark Ward, is very condescending of those who use the KJV, but his intentionally misleading statements show that the people he thinks the least of are his own readers. For example, he accuses the KJV of being archaic for using the word "commendeth" in Romans 5:8, a word which he claims has not been used in English since 1644 when John Milton used it in Areopagitica. (Apparently, Ward is incapable of using the Google Books search engine which could provide him with examples of the word "commendeth" being used in non-biblical contexts as recently as the mid 19th century.) Ward claims that a modern reader cannot understand the word "commendeth" without consulting the "massive" Oxford English Dictionary (available for online search and browsing at many libraries, but of course, Ward doesn't mention that fact). But this is also incorrect. Anyone can type the word "commendeth" into any search engine and be directed to numerous online dictionaries which provide definitions of this word. If you were to look the word up on the Your Dictionary site, for instance, it would tell you that "commendeth" is the "archaic third-person singular simple present indicative form of commend." In fact it should be fairly easy for the average English speaking person to grasp the idea that the root word of "commendeth" is "commend." Once that fact is recognized, understanding the word "commendeth" is simple. The word "commend" is a very common word in contemporary English. Google shows that this word has been used online at least 220 times just in the past month, and they found a total of 66.7 million occurrences of the word "commend" on the internet. "Commendeth" may be an archaic form of the word "commend," but it is hardly accurate to say that modern readers cannot understand what "commendeth" means without consulting 17th century manuscripts. Anyone who understands what a root word is can figure out what "commendeth" means with the help of a basic high school dictionary, and even those few who don't understand the concept of root words, can still type "commendeth" into any search engine and be provided with a definition. Ward's claim to the contrary is a sad commentary on his opinion of his own readers. 2. So why is the word "commendeth" in the KJV? One of the words in the KJV that is spurned by modern translators is the word "commendeth" that is used in Romans 5:8. "But God commendeth his love toward us, in that, while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us." The modern versions use either "shows" or "demonstrates" in this verse, but neither of those words comes anywhere close to the meaning of the Greek word that is being translated. The Greek word used here is συνίστησιν (sun-histasin). You might recognize the second half of the word as the root word of "antihistamine." This Greek word literally means "to stand by," and it conveys the idea of two soldiers standing back to back against the throng of the enemy. It is a reference to total commitment and dependability. It's similar to a phrase that was once common in the American west: "He'll do to ride the river with." This was once considered the highest compliment one man could give another. It meant that the man was totally dependable, that he would stay with you and do his job even through the most difficult rapids on the river. This is the idea that is being conveyed through the Greek word συνίστησιν in Romans 5:8, but what English word carries a similar meaning. The best English word to use here is the word "commend." This word literally means to commit to someone else's trust. It carries the idea of total dependence and reliability. We can see this in the various forms of this word that are still widely used today. For example, when a soldier receives a commendation, his superior officers are not just showing their appreciation for him. They are placing their reputations on the line and declaring that they stand by what they have said about that particular soldier. And when you recommend a particular product to your friends, you are not just showing them a product option, you are telling them that you stand by that product. That's what the word "commend" means. It means that you stand by someone that you have total confidence in that person's dependability. Both the Greek and the KJV of Romans 5:8 convey the same meaning. They both say that God's love for us is so dependable that He stood by it and did not waver even when it meant sending His Son to the cross to die for sinners. The words "show" and "demonstrate" don't come anywhere close to that idea. It needs a much stronger word, a word that speaks of commitment in spite of the cost, a word like: "commendeth." 3. Is the Bible even supposed to be easily understood? I'm still reading Mark Ward's book, Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, and it occurred to me that Paul did not write: "How then shall they call on him in whom they have not believed? and how shall they believe in him of whom they have not heard? and how shall they hear without a translation that is simple enough for them to understand fully?" Nor did he say that "it pleased God by the foolishness of easily understood Bible translations to save them that believe." Ward seems to forget that God usually provides people with help from other people who can give them the sense of the Scripture that they read or hear (Neh 8:8). I'm not saying that there is no place for updated translations, but Ward's motivation, though perhaps noble in itself, is not in line with the example of Scripture. 4. Just what is Koine Greek anyway? This selection from Mark Ward's book Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible has to be one of the most ridiculous things I've read in a long time: "There was a long period in which biblical scholars thought New Testament Greek was its own language, a 'Holy Spirit' Greek created for the purpose of getting across spiritual truths. But then two British archaeologists, Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt, went digging around in the sands of Egypt in 1896 and discovered a treasure trove of ... ancient Greek documents ... the New Testament was written in the very same language as these everyday documents. It was written in the vernacular. It was regular, common Greek, the Greek of the Greek 'plough boy.'" Now, it is true that there were some so-called scholars in the 18th and 19th centuries who tried to argue for the existence of a special language of the New Testament, but that was hardly a universal view. It was just a passing fad that gained popularity among some of the less-informed Christians of that time. The view which has been known since at least the first century BC and which has repeatedly been demonstrated to be true is the view that the New Testament was written in the Alexandrian dialect. That dialect is often referred to as Koine Greek by modern scholars, but it was not really the ubiquitous language of the common man that Ward makes it out to be. An 1823 article spanning several editions of The British Critic addressed the claim that the Greek of the New Testament was a Latin dialect of Greek and provided evidence going as far back as Lucretius in the first century BC to prove that the language of the New Testament was the Alexandrian dialect of Greek. This was the dialect spoken by Hellenistic Jews, and it was the dialect into which the Septuagint was translated. There were other dialects of Greek at that time such as the European and Asiatic dialects, but the New Testament was written in the Alexandrian dialect because that was the dialect that its authors spoke. This was not the common dialect of the Greek plow boy. There was no single dialect that spanned the entire Greek speaking world. The Alexandrian dialect, or what is now known as Koine Greek, was simply the dialect that the penmen of the Bible were most familiar with. The dialect of Greek common among the Jews from at least the 3rd century BC and onward was the Alexandrian dialect, and just about every reputable Greek scholar since before the New Testament was even written has known this to be true. Ward's attempt to make this fact into some recently-solved mystery of antiquity is just plain silly. 5. What is a unicorn? I've seen a lot of people mock the KJV for translating a particular Hebrew word as "unicorn." The modern translations use the term "wild ox" instead. But the wild ox translation does not fit the description of this animal in the Bible. The unicorn is described as a beast of immense power (Num 23:23, 24:8) that cannot be tamed (Job 39:9-10), that is very fast (Psa 29:6), and that has a single horn that is lifted high (Psa 92:1). Only the first of these descriptions could be applied to a wild ox, but all of them are consistent with a rhinoceros. By the way the Greek word used for this animal in the Septuagint is the word for rhinoceros, and the word used in the ancient Latin translations was also the Latin word for a rhinoceros. All of the evidence points to this animal being what we now call a rhinoceros but which was called in the past a unicorn. 6. What does "halt" mean? Another word in the KJV that modern translators dislike is the word "halt" which is used in I Kings 18:21. Modern translators claim that the word "limp" would be more accurate here. "Halt" is one of the words that Mark Ward categorizes as a "false friend" because he claims that it means something different today than it meant when the KJV was translated, but Ward makes several mistakes in coming to this conclusion. First, the Hebrew word does not just mean "limping" like Ward and others claim. It means "dislocated" or "wrenched out of joint." Ward mentions that this word was used to describe the lameness of Mephibosheth, but he neglects to note that Mephibosheth was unable to walk. He didn't just walk with a limp. He was incapable of walking and had to ride a donkey to get from place to place (II Sam 19:26). Second, the word translated as "leaped" in I Kings 18:26 is the same root word as the word translated "halt" in vs 21, but it is a slightly different form. It most likely refers to a halting and shuffling type of dance that the prophets performed. Third, the English word "halt" came to mean "stop" because of the fact that it refers to people like Mephibosheth who are so lame that they cannot walk. The word literally means "broken off" or "cut off." Contrary to Ward's claim, it was used as a command to stop long before the KJV was translated. The command to halt was a command to: "stop right now as if someone just cut off your leg." This is essentially the same meaning as the Hebrew word which could be more literally translated as "unable to walk because one's leg has been dislocated." 7. Should we move ancient landmarks? I'm continuing my reading of Mark Ward's book Authorized: The Use and Misuse of the King James Bible, and the next error I want to address is his claim that the word "remove" in Proverbs 22:28 should be translated as "move" instead. Ward claims that God is not talking about taking away a landmark but rather about shifting a landmark a short distance to make your field a little bit larger and your neighbor's field a little bit smaller. Ward supports this claim by saying that the word "remove" no longer means what it meant when the KJV was translated. According to Ward, the word "remove" used to mean the same thing as the word "move." It is interesting to note that Ward doesn't discuss the Hebrew text at all when addressing this issue. He asserts that the word "move" is really what God meant to say here instead of "remove" without ever considering what God actually said in the original language. When we look up the Hebrew word that is translated as "remove," we can see that it means "to move back," and at first glance, this would seem to support Ward's assertions. But if we look up the word "remove," we can see that it also means "to move back." It is composed of the word "move" and the prefix "re" which means "back." So the word "remove" is a literal word-for-word translation of the Hebrew word in this passage. But this doesn't really answer Ward's contention since he could still argue that we don't use the word "remove" to mean "move back" in modern American English, and that's true. We don't use the word "remove" in that sense today. However, a study of the Hebrew word being translated shows that it refers to more than just moving something back a few feet. In Psalm 53:3, this word is translated as "gone back," but it's not talking about moving back just a little bit. It's talking about people who have completely turned away from God. They are described as being "altogether filthy," and the Bible says that none of them do good. This is not talking about people who have moved away from God a little bit. It is talking about people who have completely removed themselves as far from God as possible. The word "remove" would be far more fitting here than the word "move." This word is used again in Isaiah 59:14 where we read that "judgment is turned away backward." Once again, this word is not saying that judgment has been moved a little bit. It is saying that judgment has been removed entirely. We can see this in the rest of the verse which says: "justice standeth afar off: for truth is fallen in the street, and equity cannot enter." Judgment and justice are not just moved away a little bit here. They are so far away that truth and equity (the products of judgment) cannot be found. The word "remove" would fit this situation much better than the word "move." We find this word again in Jeremiah 46:5 where it is used to describe total defeat. The soldiers here are said to be "turned away back," but the verse goes on to describe their turning back as "their mighty ones are beaten down, and are fled apace, and look not back." This verse is describing an army that is completely destroyed and driven out of the land. It is not describing an army that has suffered a minor setback. And once again, the word "remove" would be a better fit in this verse than the word "move." There are many other uses of this word in throughout the Old Testament, and while there are a few places where the word "move" might be used, I did not find any where the word "remove" would give an improper interpretation even if we limit "remove" to the modern sense. Thus, I don't see any reason to conclude that the prohibition against removing ancient landmarks should not use the word "remove." There is nothing in the text to indicate that God is talking about shifting the landmark a few feet. The word used seems to describe a complete or near complete removal most of the time that it is used in the Bible. Conclusion I'll probably add more to this article as friends ask me about other claims made in Ward's book. In the mean time, here is a letter that I wrote to Jonathan Beazley after reading an article that he co-authored with Mark Ward: There are several flaws in your article, and I'll try to keep this list short and to the point. 1) "We also finished our undergraduate degrees at a school that taught that the Textus Receptus (TR) compiled by Desiderius Erasmus began the process to give us the perfect preserved New Testament." That is not an accurate statement of Ambassador's position on the TR although it may perhaps be how they have worded their position from time to time. A more accurate statement of Ambassador's position would be that Erasmus continued a longstanding tradition of textual criticism to discover the preserved Word of God. The documented history of textual criticism extends all the way back to at least the early days of the church, and we have multiple examples of scholars identifying and rejecting errors in the text long before Erasmus was ever born. (Augustine, for example, compared multiple texts of the book of Genesis to determine which one gave the correct ages of the patriarchs.) The contributions of Erasmus et al. are not seen by Ambassador as the beginning of the process to discover the perfect preserved New Testament. On the contrary, Ambassador teaches that Erasmus et al. were simply bringing to light for their own generations the fact that God's perfect Word had always been available to the church. 2) "there is no perfect translation." This is merely an assumption on your part. I would agree that a perfect translation of any given statement from one language to another can be difficult, and I would even agree that the level of difficulty is compounded by the complexity of the work being translated, but a perfect translation is still at least theoretically possible. However, this point doesn't really apply to the majority of your discussion, so I'll just mention it here and move on. 3) "there is not one perfect family of Greek texts." This is a straw man argument. I'm not aware of any scholars from either side of this debate who claim that there is a family of Greek texts in which all the manuscripts agree with each other in every single detail. The entire first paragraph of your section entitled "No Two Manuscripts Read Identically" is almost offensively simplistic. The idea that there are real textual scholars who hold that some of the manuscripts are identical in every way is completely ludicrous. Scholars on both sides of the debate agree that every handwritten copy of the text of Scripture contains multiple spelling, word order, or other errors. The position of those who view the TR as the correct text is not that the manuscripts supporting the TR are free of such errors. It is that the errors in these manuscripts can be easily reconciled with each other to produce a single reading. This can be illustrated with the simple sentence, "The cat in the hat came back." Let's say that we have three copies of this sentence which read: "The cta in the hat came back." "The cat the in hat came back." "The cat in the hat cam back." Anyone comparing these three copies can easily conclude that the original sentence was "The cat in the hat came back." The fact that all three of the copies contain errors does not prevent us from using these copies to arrive at a perfect understanding of the original sentence. Thus, we can say that our textual reading of "The cat in the hat came back" is a perfect preservation of the original sentence even though we do not have a single manuscript which can be said to be perfect. 4) “how could these texts be tampered with and corrupted when many of them were buried in the sand from the second-century until the twentieth-century without any knowledge of their whereabouts?” This is simply poor scholarship on your part. We know for a fact that corruptions entered the various manuscripts very early. Origen, for example, wrote that, even in his day, an error had already been intentionally entered into the text of Luke 23:45 in an effort to discredit the claims of the Christians. And Jerome made the same claim more than a century later. The idea that the earlier manuscripts are less prone to error is pure fantasy. Instead of relying on such a baseless assumption, we should test each manuscript equally to determine which ones are correct. 5) "What this demonstrates to us is that the early churches never saw these streams as “competition” of which was superior." That conclusion is not the only one which can be derived from the evidence given, and it is directly contradicted by the historical record. As I just mentioned, both Origen and Jerome identified a specific error in some of the early manuscripts and decried it as an intentional corruption. They obviously saw those corrupt manuscripts as being in competition with the truthful manuscripts that they endorsed. A more likely conclusion from the facts presented is that the Ethiopic translators relied on the Byzantine manuscripts whenever they could and used the Alexandrian manuscripts for those portions of the New Testament for which they did not have a Byzantine manuscript. The idea that the early church simply accepted all of the manuscripts as equally conveying the true words of God is preposterous. 6) "To proclaim that the inerrant, inspired, and infallible word is found in a compiled Greek text that only acknowledges the one stream with a few nuances is actually rejecting potential authentic readings that were preserved by God from the original writers." There are two problems with this statement. First, it presents a straw man argument in the assertion that the TR "only acknowledges the one stream with a few nuances." This phrasing implies that those who hold to the TR do so without consideration of the manuscripts that differ from the TR, but that is not necessarily the case. While I am certain that there are many within the TR camp who have not taken the time to examine the manuscripts behind the Critical Text, I am also certain that there are several who have done so. The implication that the TR somehow fails to even acknowledge the other manuscripts is not accurate. Second, the claim that those in the TR camp are "rejecting potential authentic readings" is fairly meaningless. The same thing has often been said to those who hold that the Bible is the only written Word of God. I've heard many men claim that Christians are rejecting potential authentic revelations from God when they deny the inspiration of other supposedly holy books like the Koran, the Book of Mormon, or the various Hindu texts. Of course we're rejecting potential authentic readings. The whole point of apologetics is to prove that certain holy books are correct and that others should be rejected, and the whole point of textual criticism is to prove that certain readings of the Word of God are correct while others should be rejected. Saying that those who hold to one side of the debate have rejected the conclusions of those on the other side of the debate is really not saying anything at all. 7) "There is an audience today advocating that the purest Scripture did not come until 1516" This is a gross misrepresentation of those who hold to the TR. They do not believe that the purest Scripture did not come until 1516. They believe that God has preserved His Word for every generation of believers. They believe that, even though there have been many attempts to corrupt the Bible, the pure Scriptures have never been lost. They believe that God has faithfully preserved His Word and that the TR is simply one of the methods by which God has done this. "Today’s modern critical texts are based on over 5000 manuscripts dating back to the second century, with the acknowledgment of numerous ancient translation manuscripts into other languages, and numerous quotations from the Church Fathers." This is a somewhat misleading statement in that it implies that the majority of the manuscripts presently available to us support the Critical Text rather than the TR, but that is the opposite of the truth. In reality, the overwhelming majority of the manuscripts, versions, and quotations support the readings found in the TR. A mere increase in the abundance of evidence available is not sufficient to change a conclusion. It must first be demonstrated that the new evidence actually disagrees with the conclusion. 9) "However, their work was not the end of the story. Rather, it was the beginning." This is again an inaccurate view of the history of textual criticism. Christians had been critically analyzing biblical manuscripts, texts, and translations for more than a millennia before Erasmus. 10) "This is where textual criticism comes in. It understands that each variant has a unique story. And it weighs the evidence to see which reading would best represent the original writing." We actually agree in regards to the necessity of textual criticism. It is important to "weigh the evidence to see which reading would best represent the original writing." That is something that Christians have been doing for nearly 2,000 years. Where the supporters of the TR and those who favor the Critical Text differ, however, is over the criteria against which the various manuscripts are to be measured. In general, those favoring the Critical Text take the position that the readings found in the earliest manuscripts are the most reliable while those favoring the TR take the position that the readings found in the majority of manuscripts are the most reliable. Of course, the two positions are both more nuanced than this simplification, but the fact remains that the primary point of contention between the two views is the criteria by which the accuracy of the various manuscripts is determined. I would recommend that you focus on this key difference as you continue your series. By the way, let me hasten to add that I do not intend for any of my comments to be offensive or belittling in any way. I disagree with the two of you in this one particular area, but I certainly don't hold that against you as individuals. Disagreements of this type are necessary and beneficial to the body of Christ since iron cannot sharpen iron without the frequent assistance of friction. Addendum in Response to Mark Ward's Comment Below: Hi, Mark. Thank you for responding. I appreciate your willingness to condescend to my lowly level of blogging. Unforunately, your response has done little to improve my opinion of your book. (1 and 2) In regards to the use of the word "commendeth" in Romans 5:8, I'll only add that I recommend (you do understand what recommend means, right?) consulting the LSJM in addition to the BDAG to get a better understanding of συνιστημι. The LSJM uses a broad literary base to provide a list of meanings for this word that includes: set together, combine, associate, unite, organize, frame, contrive, meet and form a triangle, compose, bring together as friends, introduce or recommend one to another, make solid, brace up, exhibit, give proof of, prove, establish, to be joined, form a union, band together, and etc. The common thread that joins all of these meanings is, as I pointed out, the idea of two or more things standing by each other. The word "commend" or "commendeth" is an accurate and understandable translation of συνιστημι in Romans 5:8. I do not consider this to be the only acceptable translation. There are other English words that could be used. The word "proved," for example, would do well here as would the word "confirmeth" as Charles Thomson translated it. But the words "show" and "demonstrate" are insufficient to convey the meaning of the Greek. (3) I'll admit that my third section was not as fully developed as I would have liked it to be. If you'll recall, these are just random Facebook posts about your book. I was challenged on this section by someone else yesterday, and I devoted some time to developing it further. Here is what I wrote in response to that challenge: As for section 3 of my article, the point that I used those verses to make is that the Bible itself says that God uses individual people to help other people understand the Bible more accurately. I was not arguing against translation. That should be obvious since I was making that argument in defense of a translation. I was arguing against the idea that a translators primary goal should be to make the Bible easy to be understood. The translator's primary goal is to be accurate lest he be guilty of changing the Word of God. It is the responsibility of individual Christians to take that accurate translation and help others understand it. For example, the Ethiopian eunuch in Acts 8 was confused because of the ambiguity of the pronouns in Isaiah 53. God could have told Philip to write a new translation with less ambiguity, but that's not what He did. Instead, He had Philip provide personal instruction for the eunuch, and that was sufficient for the eunuch to understand and accept Christ. This is the pattern that is found in Scripture. When someone desires to understand the Bible, God sends another Christian to explain it. There is no Scriptural support for the claim that a translation must be easily understood. The goal of the translator is to be accurate, and he is always to choose accuracy above comprehension. Additionally, the KJV is not that hard to understand in the first place. I've read well over 10,000 books, and there is not a single book written for adult readers that only uses words that every English speaking adult understands. The best selling books always use challenging vocabulary with most of them using words that have been denounced as archaic. In fact, the best selling book of all time (outside of the Bible) is written in mid-nineteenth century English and is filled with archaic words and phrases. Yet modern adult readers have no difficulty at all figuring out what Charles Dickens meant when he used words like "incommodiousness." The vocabulary of the KJV is easier to understand than that which is found any of the books by Charles Dickens. The difficulty in comprehending the Bible is not a translation issue. It is a product of the complexity of the concepts that the Bible teaches. Einstein's book "Relativity: The Special and General Theory" can only be simplified so much before it begins to fail in teaching the concepts that Einstein wanted to convey to the world. That is simply the nature of complex thought. Certain ideas and concepts cannot be simplified enough to be understood by the average reader, and the Bible is filled with such ideas and concepts. There will never be a translation that can overcome that difficulty. That is why God chose to use human individuals to explain those concepts to others. (4) I am not arguing against Deissmann's basic position. I'm arguing that the position didn't originate with Deissmann. It was known long before Deissmann came on the scene that the language of the Bible was a common dialect of Greek that originated in Alexandria and became the dominant dialect in Alexandria and Asia Minor. This is not some new discovery that was unkown to the KJV translators. You attempted to dismiss my source as being "pre-Deissmann and therefore pre-papyri," but Deissmann didn't use the papyri to understand the language of the New Testament. He used the papyri to understand the language of the Septuagint. Deissmann claimed that "the Papyri are of the highest importance for the understanding of the language of the LXX." Regarding the New Testament, on the other hand, Deissmann said that "just as we must set our printed Septuagint side by side with the Ptolemaic Papyri, so must we read the New Testament in the light of the Inscriptions [of the imperial period]." Deissmann's understanding of the Greek used in the New Testament didn't come from his study of the papyri; it came from his study of the inscriptions found on the architecture from that time period. Thus, even your own source notes that a proper comprehension of the language of the New Testament is not dependent on the discovery of the Egyptian (ie: Alexandrian) papyri. As a side note, it is important to keep in mind that Deissmann was no friend to conservative Christianity. He was adamantly opposed to the idea that the Bible is the Word of God. One of his stated goals was the eradication of the doctrine of verbal inspiration. He expressed this goal rather eloquently in his book on Bible Studies: "The doctrine of verbal Inspiration, petrified almost into a dogma, crumbles more and more to pieces from day to day; and among the rubbish of the venerable ruins it is the human labours of the more pious past that are waiting, all intact, upon the overjoyed spectator ... But much still remains to be done before the influence of the idea of Inspiration upon the investigation of early Christian Greek is got rid of." And in his book New Light on the New Testament, Deissmann wrote: "In the judgment of the present writer there is but one answer possible ... namely, a decided affirmation that the letters of St. Paul are not literary, that they are genuine familiar letters, not epistles, not written by St. Paul for publication and for after-ages, but simply for those to whom they were sent ... after the death of St. Paul they arose to the dignity of literature, literature in the exalted sense of canonical literature. But that is purely an incident in the subsequent history of the letters ... St. Paul had no intention of increasing the existing number of Jewish Epistles by a few new writings, and still less did he think to enrich the sacred literature of his people ... He never dreamed of the destiny in store for his words in the history of the world, and had no idea that they would be in existence in the next generation, still less that they would one day become Holy Scriptures to the nations." Given Deissmann's approach to the Scriptures, it would be wise to take all of his conclusions with a grain of salt. (5) I was only addressing your book tangentially in this particular Facebook post. I'm glad to hear that you agree with me. (6) I am sorry that you find it confusing. You might benefit from doing an etymological study of the English word "halt." (7) Again, I'm sorry that you are unable to follow my argument, but I'm not sure that I can simplify it any further for you. The last two sentences in this section provide a pretty good summary of my view. (Conclusion) I suspect that your difficulty in understanding my previous sections is partly due to you giving my entire article only a light reading without paying attention to the details. This suspicion is strongly supported by the fact that you criticized me for including the topic of textual criticism in my "review" of your book. If you had given my article a more thorough consideration, you would have noticed that "as I stated clearly and repeatedly, ... brother," my discussion of textual criticism was a response to an article that you co-authored with Jonathan Beazley. You accused me of struggling to stay on the topic of readability, but it's clear that you struggle with just plain reading in general.

2 Comments

A friend sent me this post today. You do not have to post this comment. Feel free to reply via email or to simply ignore this reply.

Reply

Bill Fortenberry

4/16/2023 07:20:43 am

Hi Mark. My response to your comment was too long for the comment section, so I added it as an addendum to the original article above.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Bill Fortenberry is a Christian philosopher and historian in Birmingham, AL. Bill's work has been cited in several legal journals, and he has appeared as a guest on shows including The Dr. Gina Show, The Michael Hart Show, and Real Science Radio.

Contact Us if you would like to schedule Bill to speak to your church, group, or club. "Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser: teach a just man, and he will increase in learning." (Proverbs 9:9)

Search

Topics

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed