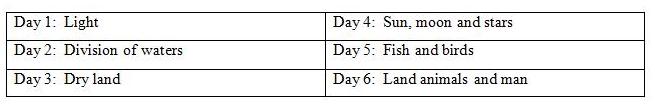

In the previous article, I explained why I view the first two chapters of Genesis to be of the same genre as the rest of the book. There are, of course, several arguments which are brought against this view, and I’d like to briefly address a few of them before moving on. The first objection to my view is the claim that the order of the creation days reveals parallelism which is a feature of Hebrew poetry. This parallelism is supposedly seen in the fact that the days of creation are divided into two sets of three days and that the events of those two sets parallel each other as seen in the following table. The parallel order seen in this table is undeniable. For some reason, God chose to create places first and then to create things to fill those places in the same order. However, this is not an example of Hebrew poetry.

The claim that this parallel structure is poetic reveals that those making this claim are unfamiliar with the genre of Hebrew poetry. The parallelism of Hebrew poetry is not a parallelism of structure; it is a parallelism of thought. English poetry is based on its structure. Every line of the poem must match a certain rhythm of syllables and the words at the ends of the line usually match a set pattern of rhyming. In Hebrew poetry, however, the structure is inconsequential. The key to properly writing Hebrew poetry is to use two or more parallel thoughts to convey a single expression. When we compare the creation account in Genesis 1 with the account in Psalm 33, the difference between parallelism of structure and parallelism of thought becomes very obvious. Let’s begin with the first five verses of Genesis 1: In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness. And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. Now let’s compare this with four verses from Psalm 33: By the word of the LORD were the heavens made; and all the host of them by the breath of his mouth. He gathereth the waters of the sea together as an heap: he layeth up the depth in storehouses. Let all the earth fear the LORD: let all the inhabitants of the world stand in awe of him. For he spake, and it was done; he commanded, and it stood fast. (Psalms 33:6-9) As you can see, each of the four verses from Psalm 33 is composed of two thoughts which are very similar. “By the word of the LORD were the heavens made” says basically the same thing as “all the host of them [were made] by the breath of his mouth.” The thoughts expressed in these two lines are parallel to each other, and taken as a whole, they convey a single idea: God spoke the heavens into existence. This pattern can be seen in each of the four verses. The first line expresses a particular thought; the second line expresses a similar thought, and the two of them together convey a single concept to the reader. This is what Hebrew poetry looks like. In contrast, the creation account in Genesis 1 has an obvious parallel structure in the order of the events, but there is no parallelism of thought in this chapter. Let’s just take the first verse, “In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth.” Where is the parallel thought for this verse? The closest verse that conveys a similar thought to this one is found all the way over in the next chapter where we find verse four mentioning “the day that the LORD God made the earth and the heavens.” These two thoughts are far too removed from each other to be considered part of the same poetic expression. But what about the parallel days of creation? Don’t they prove that this passage is poetic? Well, why don’t we rearrange the phrases in Genesis 1 in such a way that the phrases which are parallel to each other are placed together just like they are in Psalm 33. Here’s what that would look like: God said, Let there be light: and there was light. Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters. Let the waters bring forth abundantly the moving creature that hath life, and fowl that may fly above the earth in the open firmament of heaven. Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: Let the earth bring forth the living creature after his kind. From this arrangement, it is obvious that the only verse of this construction which could be viewed as conveying a parallelism of thought is the first one. It is possible that the phrase “Let there be light” could be parallel to the phrase “Let there be lights.” These two could be expressing the single thought that God spoke all the celestial bodies into existence. But this is the only verse which can be viewed in this manner. The phrases in the remaining two verses are jarringly non-poetic. There is no parallelism between “Let there be a firmament” and “Let the waters bring forth abundantly.” The first phrase conveys the thought that God separated the waters. The second thought is that God created living creatures. These thoughts are not parallel. There is no single thought which can express the idea being conveyed by these two lines. One could attempt to combine the two by saying, “God created sea and sky and filled them with life;” but this is just a double thought expressed in a single sentence. No matter how we rearrange the words, the fact that Day 2 and Day 5 convey two completely distinct thoughts is inescapable, and days 3 and 6 have the same problem. Thus the argument that Genesis 1 contains Hebrew poetry falls flat on its face. Hebrew poetry is based on the concept of parallel thoughts. Genesis 1 does display a parallelism in its structure in that the days of creation can be arranged into two parallel sets of three, but there is no parallelism of thought in this chapter. Therefore, Genesis 1 cannot be an example of Hebrew poetry.

1 Comment

interesting...I've never heard this point being made before. Another thought about parallelism...when thinking about parallelism in terms of lines we know one eqivocal fact about parallel lines, they will never cross. That being said, if we have two straight parallel lines leading to somewhere only 1 line will lead us to our destination. The same goes for religions and beliefs. If there is one true religion and many that parallel it only one will lead us to our destination.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Bill Fortenberry is a Christian philosopher and historian in Birmingham, AL. Bill's work has been cited in several legal journals, and he has appeared as a guest on shows including The Dr. Gina Show, The Michael Hart Show, and Real Science Radio.

Contact Us if you would like to schedule Bill to speak to your church, group, or club. "Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser: teach a just man, and he will increase in learning." (Proverbs 9:9)

Search

Topics

All

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed