|

Much of the debate on the relationship between church and state has centered around the phrases “freedom of religion” and “separation of church and state.” While these phrases have a very important history and should be studied, their applicability to American government must be understood within the confines of the First Amendment. Unfortunately, the debate on this Amendment has largely focused on whether or not its prohibitions are limited to the US Congress. The real key to understanding the First Amendment lies in unlocking the mystery of the phrase “an establishment of religion.”

0 Comments

Conservatism is the philosophy that the wisdom of the past is still just as applicable today as it was then. Conservatism is an ancient wisdom in itself, for every age has its conservatives and liberals, and it is always the conservatives who succeed and pass their wisdom down to the next age where some new brand of liberals will rise up to challenge that wisdom once again.

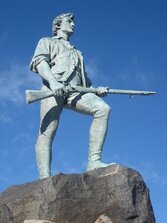

It has become rather common in our day to hear descriptions of our founding fathers as bold rebels daring to defy the authority of the British government, but is that really what happened? Was the American Revolution an act of rebellion against England? That has certainly become a popular theme in modern, American education, but the records of the founding era tell a different story. I recently had the opportunity to listen to a debate between Mark Hall and Steven Green on the topic of the Christian foundation of America. Hall has written a book defending the idea that America had a Christian foundation, and Green has written a book in defense of the opposite view. I obviously agree with Hall, but I thought that he could have done a better job of refuting some of Green’s claims (and he probably does so in his book). Since I was taking notes anyway, I thought that I would share a few of my objections to Green’s claims.

Modern accounts of the philosophical underpinnings of the American Revolution often attribute the concept of popular sovereignty to men such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau with Locke being the one most often praised as the source of the American ideal of a government of the people, by the people and for the people. To make this attribution, however, modern scholarship has had to ignore or, perhaps, forget the previously held view that the notion of popular sovereignty can be traced to the government of ancient Israel as recorded in the pages of the Bible. This in-depth study is an attempt to correct that error.

The conclusion to my book Hidden Facts of the Founding Era contains a list of 49 correlations between the Bible and the Constitution, and I thought it would be good to share it again here. The book is a refutation of Chris Pinto's popular video The Hidden Faith of the Founding Fathers, and it is written for a homeschool audience. You can read the conclusion here, and of course, the book is available on Amazon.

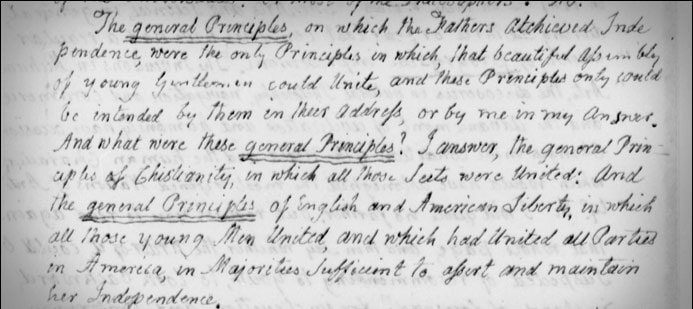

One of the major points of contention in the discussion of America’s Christian foundation is found in a reference that John Adams made to the “general principles of Christianity.” Those who support the idea that America was founded on Christian principles often present this statement as evidence in their favor, while those who disagree with them usually respond by pointing to the context of the statement as evidence for their position. Unfortunately, most of those discussing Adams’ statement seem to be operating under the impression that it was made in a vacuum. In this article, I will attempt to provide a full analysis of Adams’ letter and demonstrate that when we consider all of the variables in their proper order, it becomes clear that this letter supports the claim that America was founded on principles that are unique to Christianity.

Ever since the Constitution was first submitted for ratification, the final clause in Article VI has been a matter of strong contention among Americans. That clause, known as the religious test clause, simply states that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.” It is frequently claimed that this clause represents the desire of the founding fathers to keep religion out of the government and to establish a secular nation. But is that really how this phrase was intended to be used?

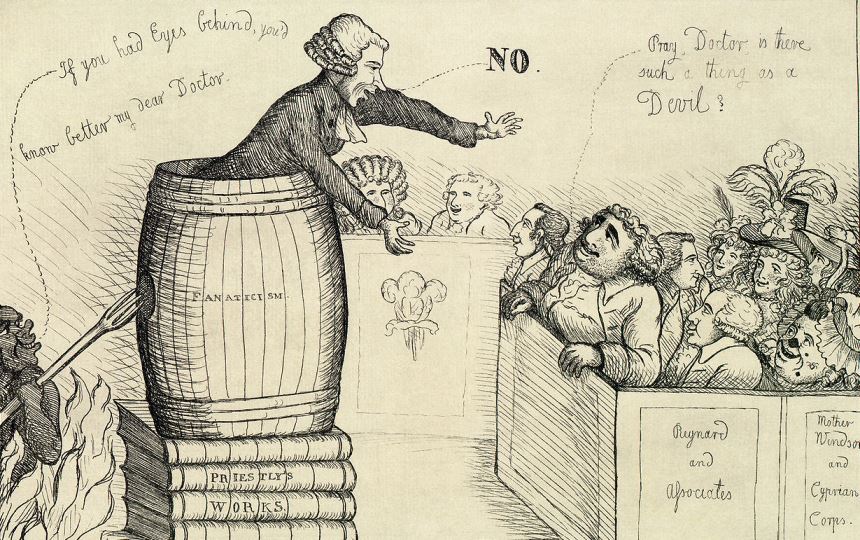

In reading Gregg Frazer’s book on the founders, his high estimate of Joseph Priestley’s influence on the founding fathers is clear and blatant. Early in the book, Frazer writes that “It would be difficult to overstate the importance of Priestley to the development of the political theology of the American Founding.” In speaking of John Adams in particular, Frazer writes that he was “heavily influenced” by Priestley. Frazer further insists:

When discussing John Adams’ beliefs regarding the Bible, Frazer presented two references to an often quoted letter that Adams wrote to his friend Francois Van der Kemp. Frazer claimed that this letter is evidence of John Adams’ theistic rationalism because it presents both Adams’ acceptance of some revelation and his belief that the Bible is filled with fables. Unfortunately for Frazer, the letter in question does not support his claim that Adams believed the Bible to be filled with fables. |

Bill Fortenberry is a Christian philosopher and historian in Birmingham, AL. Bill's work has been cited in several legal journals, and he has appeared as a guest on shows including The Dr. Gina Show, The Michael Hart Show, and Real Science Radio.

Contact Us if you would like to schedule Bill to speak to your church, group, or club. "Give instruction to a wise man, and he will be yet wiser: teach a just man, and he will increase in learning." (Proverbs 9:9)

Search

Topics

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed